Status of Southern Corn Billbug in NC Blacklands

go.ncsu.edu/readext?829321

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲Southern corn billbug is a historical pest of corn in the southeastern US and, in North Carolina, was a persistent pest throughout the Coastal Plain. Nearly 100 years ago (1917), a biologist named Z.P. Metcalf published a technical bulletin describing its biology and even used an insectary dedicated to rearing southern corn billbug. A century of drainage, land development, and improved weed control likely decreased the prevalence and range of this pest. Interest in its biology waned, as researchers moved onto other more important pests. Finally, the widespread deployment of corn seed treated with clothainidin (Poncho 1250) in the mid-1990’s almost rang the death knell for this pest, as insecticide-treated corn knocked back populations that were still persistent in the North Carolina Blacklands region.

Growers are well-aware of how reliance on a single tactic (insecticides) and a single mode of action within that tactic can lead to failure. Indeed, what is old is new again, as southern corn billbug populations have increased in both number and expanded in range.

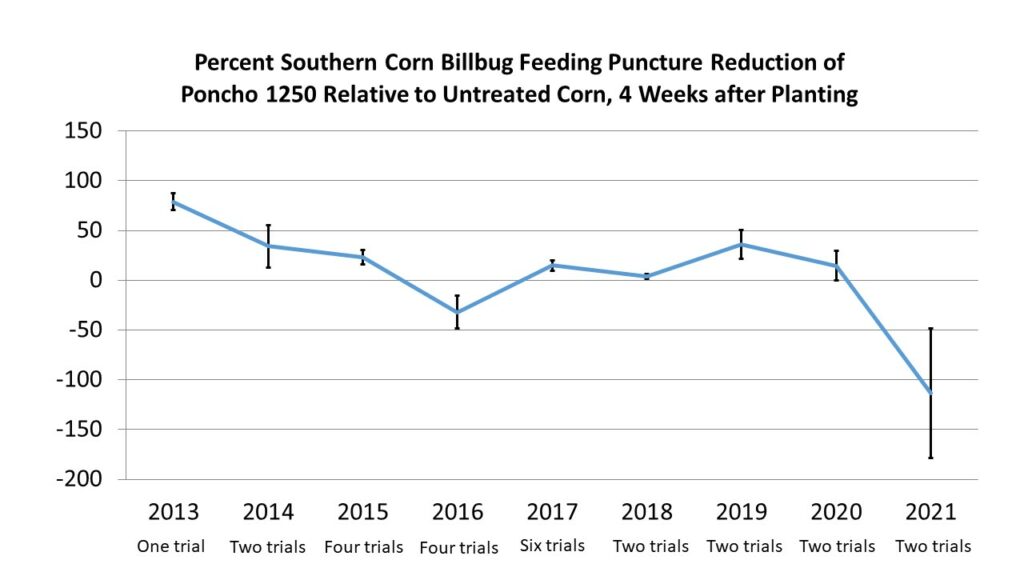

Percent southern corn billbug feeding puncture reduction of Poncho 1250 relative to untreated corn, 4 Weeks after planting. Note that these data represent the percentage of plants with any sort of puncture from southern corn billbug and are not a measurement of feeding severity. Data are taken from replicated small plot trials.

2021 was a lower-pressure year in our plots. On average, around 6% of the plants were fed on by billbugs. In comparison, nearly 100% of the plants were fed on by billbugs in untreated plots during 2017. Despite this difference in pressure, more plants were fed on in plots treated with Poncho 1250 compared to untreated plants during 2021. The figure above clearly indicates that the efficacy of clothianidin (Poncho) is decreasing over time.

What else are we seeing?

Increasing adult feeding in corn is a result of higher populations that develop in corn. In tandem, we have noticed that more larvae are developing in the crown of corn. An astute grower noticed that many of his plants were senescencing earlier than neighboring plants. When he pulled these plants up and split the crown, there was clear evidence that billbug larvae had developed in the early-senescencing plants. Visually, ears from these plants looked smaller than plants without evidence of billbug larval development.

In addition to hampering seedling development from adult feeding, larvae seem to be causing a direct yield loss by reducing ear size.

What can be done?

Our insecticide screening trials for southern corn billbug have investigated nearly every labeled insecticide for foliar, in-furrow, and seed-applied usage in corn. A major barrier is that this issue is very specific to the North Carolina Blacklands (perhaps 10,000 to 20,000 acres are billbug hot spots). The development of most corn insecticides is targeted toward a more widespread soil pest, western corn rootworm. These rootworm insecticides do not cross over well to manage southern corn billbug. Other major challenges are poor insecticide efficacy in the high organic and often saturated soils of the Blacklands, the life-stages of the pest needing to be managed, the cryptic nature of the pest, the lack of rotation in the landscape (corn usually borders where corn was planted last year, even in rotation), and the availability of alternate hosts in both crop (yellow nutsedge is a host) and non-crop areas.

One company is working on a label for a product that growers can apply in-furrow. However, it is the same active ingredient as the seed treatment (clothianidin) and performance is variable. Therefore, it is not a good long-term option. Prior to seed treatments, growers relied on Counter (terbufos). Indeed, Counter has improved performance, especially in combination with Poncho-treated seed, in our trials. However, we have documented stand loss with higher rates of clothianidin (Poncho 1250) and only recommend that growers use Counter in-furrow with Poncho 500. Counter is undergoing re-registration with the US EPA and its long-term status is questionable. Many insecticides in this class have already been removed from the market and it will not be available long-term.

For the time-being, growers should check billbug-affected areas for signs of larval development later in the season. These areas can be identified as potential target areas for the use of Counter + Poncho 500. Long-term, growers need to think about a rotational strategy to minimize billbug populations by moving away from corn. Not that it will be easy, but corn should be planted at least 1,000 feet away from last year’s corn (based on results from Wright et al. 1993). This includes considering the timing of their rotation with that of their neighbors. Other useful management strategies that growers already employ include starter, proper seed placement, proper drainage, and good weed control. The goal is to promote early seedling growth to outrun any billbug damage the seedling might sustain.